Επιμέλεια: Εύα Πετροπούλου Λιανού

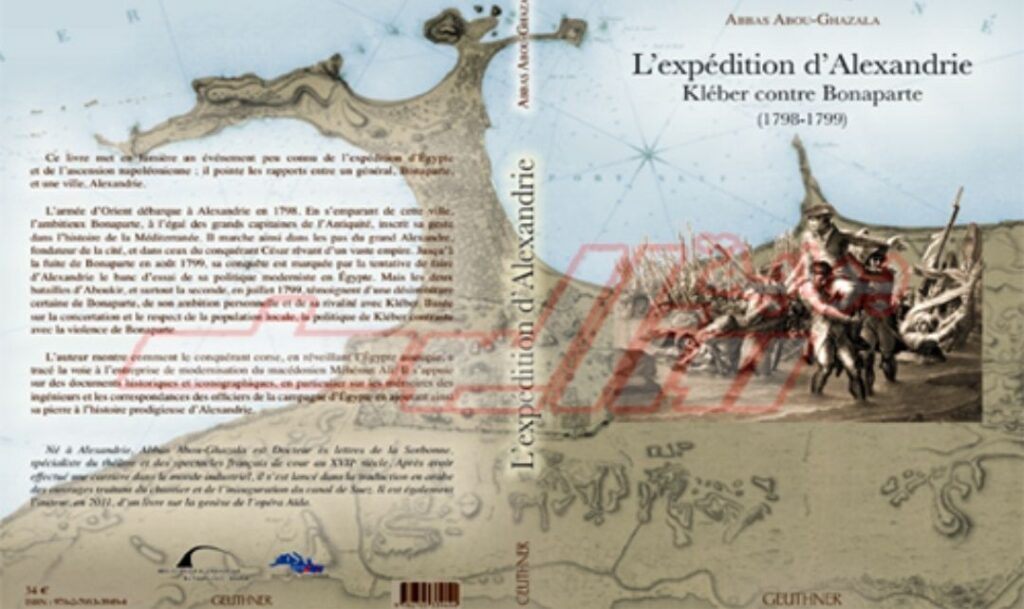

This book, The French Campaign against Alexandria, “Cléber Against Bonaparte,” 1798-1799 AD, by Professor Dr. Abbas Abu Ghazaleh – and the book is in French – sheds new light on an important and unknown event at the beginning of the French campaign against Egypt (1798-1801), during the rise of Bonaparte’s star. With the glories of his victory in Italy. Following in the footsteps of the great conqueror Alexander, the founder of the city, and in the footsteps of Emperor Julius Caesar, Bonaparte tried to restore their ambitions in his occupation of Alexandria. Bonaparte wanted to make Alexandria the place of choice for his policy aimed at modernizing Egypt, given the importance of the location of the city to which supplies and war ammunition needed for the troops would arrive. The character of Napoleon, who was called Bonaparte in Egypt, represents the legend of a French hero and adventurer, and his wars are still taught in military academies. The book “Description of Egypt” is an unparalleled encyclopedia, which was co-prepared by the campaign’s scholars. Bonaparte succeeded in attracting – in addition to the army forces – one hundred and sixty-seven scholars from various sciences, arts and literature, and this was a unique event in the history of wars.

The limits of the study:

The campaign began in July 1798 AD, and the French army left Egypt on September 14, 1801 AD. The duration of the campaign was three years and two and a half months. The events in Alexandria imposed the limits of the study, and the writer chose the beginning of July 1, 1798 AD, the day the campaign armies arrived and landed near the Agami beach at “Sharm Al-Murabit” in the port of Alexandria, led by Bonaparte, and until August 22, 1799 AD, which is the day on which Bonaparte secretly left, to return to France, Leaving the leadership of the campaign to his rival, Clipper..

The book presents the competition between Bonaparte and Kléber in managing the campaign, and analyzes the many battles that the French army fought, and the various methods of persuasion and intimidation that the French leaders used with the people to subjugate them. We follow the conflict within the Eastern Army after the “Abu Qir” disaster, in which France lost its naval forces, as “Kleber” opposed the attempt to equip the naval forces in which he saw no hope..

Content of the book:

The book highlights an important aspect of Bonaparte’s adventure, which involved France in a war without full preparation, and without having control over the Mediterranean. Bonaparte bears responsibility for the failure of the military campaign, and the disaster of the Abu Qir naval battle. The testimonies support that Bonaparte led the campaign to be absent from France, waiting for the appropriate opportunity to return to it. The evidence for this is that he left Alexandria secretly after a year, to become consul after the eighteenth century (Premier) coup against the administration government in France. He had issued an order appointing Kleber as commander of the Army of the East after him, even though the latter opposed the policy of oppression and intimidation, criticized his ambitions, and was against the occupation in accordance with the principles of the French Revolution and the culture of the Enlightenment.

The position of the administration govern:

In 1795 AD, Charles Magallon, the French Consul General in Cairo, explained that conquering Egypt was easy, and that the country offered countless advantages. The response of La Croix, the Minister of Foreign Affairs at that time, was that the opportunity had not yet arrived, and that any project regarding Egypt must be waited for. After two years, the administration government found a way to remove the ambitious Bonaparte and accept the invasion of Egypt. Bonaparte had spent four months since his return from the Italian campaign, crowned with victory, and was ready to leave Paris. He made hasty preparations for his departure while awaiting the decision to leave Paris..

Preparations:

Bonaparte chose the most important commanders whom he described in his memoirs: General Cavarelli, General Kléber, General Menou, General Dézier, and General de Martin. As for Cafarelli, he was a capable and experienced warrior. He was distinguished by his knowledge of public administration methods, a loyal friend, and a loyal citizen. Cafarelli worked as director of the committee of scholars and artists that accompanied the campaign, and he was so active that we did not realize he was missing a man whom the Egyptians called (Abu Khashaba).

As for “Kleber”, he was the most beautiful of the army commanders, and he was forty-five years old. He served eight years in the army of Austria (Germany), and was distinguished by his clear mind and courage. He was also a mighty warrior with his deeds and exploits, so much so that he was called: “The God of War, Mars.”

This large army, which included more than thirty-two thousand warriors, six hundred and thirty horses, and one hundred cannons, had to cross the Mediterranean, in addition to weapons and equipment, and supplies sufficient for three months.

Add to this the Maltese prisoners, and eight hundred Maltese Turkish prisoners, who were liberated by the French army to be returned to their homeland, and were serving on French ships.

Bonaparte supervised the preparations, and the preparations were completed in a few weeks. The troops sailed from five ports. Admiral Brewis prepared the fleet and assembled ships for this new campaign. He brought out ships in poor condition, such as: (Le Guerrier et le Conquérant). The crowding of ships loaded with teams and equipment made it dangerous, if necessary, to fight, and the equipment was not sufficient, and the matter was not completely reassuring according to the testimony of the soldiers, as they witnessed the improvisation that was the reason for the defeat of the war campaign, and the navy in particular.

Secret itinerary:

In a period not exceeding several weeks, Bonaparte prepared the campaign, the purpose of which was not announced. The name of the army remained “The Army of War against the British.” The Secretary of the Administration was not assigned to write the departure order, but the Prime Minister of the Administration did so himself. Bonaparte and the directors of the administration kept the secret, and the government did not announce the campaign to the public. Thus, the commanders, including generals and ship commanders, were unaware of where the campaign was directed.

In April, the Admiral, the commander of the fleet, wrote to Bonaparte, asking him to know the direction in preparation for the quarantine measures. He said: “Everything must reach me a few days before departure, and it is necessary that I know the nature of the campaign in order to take all measures. No one cares about the matter more than me.” So he keeps the secret, and I can keep the secret without risk.” The Minister of War himself asked to hide the itinerary and final direction, and many believed that the goal of the campaign was East India, crossing the Gulf of Suez, and crossing the Red Sea… Despite all the precautions taken to keep the campaign secret, the news reached Alexandria in early May, and the French population was reassured.

Bonaparte during the voyage:

Bourienne writes in his memoirs that Bonaparte enjoyed spending time talking to Monge, Bertollet, and Caffarelli. The conversation revolved around chemistry, mathematics and religion. Bonaparte spent most of his time in his room on a four-legged walker with a moving wheel, so that he would not feel seasick. After seizing Malta in seven days, marching to Kandy for seven days, and spending another four days to the coast of Africa, and after eleven days of journey, the fleet arrived in front of Borj el-Murabit, ten kilometers from Alexandria. On the morning of the first of July, the army discovered the city of Alexandria.

Urgent disembarkation from ships:

When Bonaparte learned of the presence of the English nearby, he issued the order to disembark the army at Almoravid, even though he wanted to enter the delta through the two branches of the Nile at the same time as capturing Alexandria.

The landing conditions were very difficult, the sea surface being low and shallow, and to avoid the chain of rocks visible on the surface of the water, it was necessary to anchor far from the shore. The naval architecture remained at sea to protect the landing of troops for fear of enemy attack. Moreover, the waves were high, the sea was rough, and the winds were strong. There was no knowledge of measuring the passages between the rocks.

Admiral Bruys tried to persuade Bonaparte not to land troops in these difficult circumstances, but the Commander-in-Chief did not respond, and

Risked the lives of his men:

Admiral…We don’t have much time. I’m lucky enough to have three days. If we don’t take advantage of them, we’ll be doomed.”

Bonaparte feared that the city and its suburbs were ready to confront the French. The army was in a critical position, and the admiral gave the signal for boats, large boats, and rescue boats to disembark on Al-Morabit Island. Al-Amara sailed in front of Alexandria, approximately ten kilometers from the coast (about two parasangs). The troops were disembarked at eleven o’clock in the evening, and it was difficult to disembark the horses, and they were taken by floating from inside the boats. Correspondence officer Nilo Sarji says that thirteen days after leaving the port of Toulon, the fleet arrived in Alexandria at eight in the morning and saw the city’s minarets.

Resistance:

Resistance began when approximately one hundred Bedouin Arabs and three hundred horsemen came to attack the troops as they left the ships. The Arabs of the Al-Hanadi tribe, riding their horses, attacked the latecomers as if they were terrifying monsters. At night, a Bedouin cavalry group surprised a vanguard of the army and killed Captain Moreau. It is said that they cut off his head and returned with it in triumph on the streets of Alexandria. As soon as he finished disembarking his squad, Dizé was attacked by the thirty Bedouins who came and surrounded him. They killed three men and captured five or six.

Attack on the city:

The attack on Alexandria began after the teams landed, and the city was ready to repel the French invaders as soon as they arrived, and the Bedouin knights pursued the teams as they left the ships.

Bonaparte led his forces towards Alexandria, and three divisions were formed to form the attack line. Each division headed towards the heights surrounding the city of the Bedouins. Despite this, a group of Bedouins was able to circle around them and attack them from behind.

The three teams started marching at 2:30 in the morning. The weather was hot, and the soldiers were walking through the scorching sand of the desert. The thirst increased, and Truman wrote in his diary: “I wished I could give ten years of my life for a cup of water.” As for Bonaparte, they found an orange brought by a soldier from Malta.

The divisions arrived at the city walls at nine in the morning on July 2, and began the attack. General “Mino” was on the left wing, walking along the sea, with two thousand five hundred men, and in the center was General “Kleber”, with a thousand men. General Bon headed with his forces of one thousand five hundred men to the right wing towards Bab Rashid.

Bonaparte had five thousand soldiers with him, and he walked on foot because not a single horse had been dismounted from the horses coming with the expedition. He headed to the Pillar Column, and climbed the base of the Pillar Column to reconnoiter the city and prepare the campaign. He sent some officers to inspect the fortifications in the wall of the Bedouin city near the new city, and all the old cracks appeared to have been restored.

At the same time, all of the commanders, René Houdizier, finished disembarking their teams from the ships in Al-Murabit Bay and headed to the city. The army left the artillery and horses and began the attack without these weapons.

Capture of Alexandria:

The French fleet arrived in front of Alexandria, and anchored Qitaf. Some Frenchmen disembarked looking for the consul and other people, and towards night the ships headed towards Al-Ajami Castle, and the soldiers and their equipment disembarked from them. The next day, the French spread like locusts around the city, and the Alexandrians attacked the French, followed by those who came from the lake with Al-Kashef. When the people of the Thaghr and the Arabs who joined them came out together and discovered the lake, they were unable to deter them.

The truth is different if we go back to the testimony of Souhait, the chief of engineers: “We left the city to avoid bloodshed, to no avail.”

The army arrived at the city walls, and was exposed to Turkish cannons and bricks thrown by the Bedouins from rooftops and from inside homes. The residents were firing several rifles, killing 150 men from among the three squads. Both the Clipper and Menno divisions suffered heavy casualties, and General Menno and General Clipper were wounded by bullets that came out of the fences and houses. These losses could have been avoided if the city had been warned, but Bonaparte wanted to surprise the residents and create terror among them. The Turkish defenders who fired from the windows were pursued, some hid in castles, others in mosques, men, women and the elderly were annihilated, and the French soldiers ended the massacre after four hours of attacking the city. The Alexandrians defended stubbornly, and the inhabitants around the walls were firing fiercely, but when the French arrived in front of the walls, instead of firing, they hurled a shower of stones at them.

When the French were able to climb the walls, those behind the walls were forced to flee, while those in the towers – despite the others’ escape – did not stop unloading the rest of their weapons on the French. One of the city walls was controlled, and part of the teams entered the new city, and another part entered the citadel (Al-Fanar) and the lighthouse (Al-Silsilah), where part of the army forces took refuge in Alexandria.

The French commander Sanson describes: “The people were fighting desperately and feverishly, and they did not know our intentions and principles.” This indicates the deception of the soldiers who came with Bonaparte in the name of enlightenment and protecting the Egyptian people from the oppression of the Mamluks. Bonaparte headed to a summit controlling the city and the port, to gather the army, but the people’s boldness and stubbornness sparked the French forces’ enthusiasm, and an exchange of bullets occurred.”

Bonaparte wrote to the administration’s government: “Every house was a castle,” and added in his report: “While we were holding the castles, the Arabs of the desert came from behind to attack the trailing comrades, and they did not cease pursuing us for two days.” After responding to the aggression, the population quickly hid supplies from the French enemy, causing food scarcity and famine. But after concluding peace with the notables of the country, the goods that the country abounds were again available to the French, including chickens, geese, pigeons, cows, and animals that the country produces in abundance.

Among the funny things we mention is what was recorded by Commander Bertrand, who participated in writing Bonaparte’s memoirs in St. Helens: “During the attack, Bonaparte chose a high place (L’observation), which he called Kafrilli Castle (Kom Nadora). With curiosity, General Bertrand headed toward Eager to get to know Commander Bonaparte closely, whose victories the world talks about, and who left an impression on the people’s imagination, Bertrand quickly went up breathless to see the famous general and found him sitting on the ground with his back turned to the attack of the forces on Alexandria, and he found him striking with a hammer the remains of a ceramic stone that formed the height. It is available in Alexandria, Cairo, and the villages of Egypt, and when an officer from General Mora came to him and told him that the people had taken refuge in Al-Fanar Castle, he asked him to bring the sheikhs and notables of the country to conclude peace.

Reconciliation agreement:

On the fourth of July, the Alexandrians sent delegates to sign peace, and discussions took place about implementing the law of the people of the country and its religious institutions, applying justice, and that the delegates work for the good of the country and the happiness of the population, and eliminate the evil Mamluks, and not betray the French army and harm its interests, and participate in plotting conspiracies against it.

For his part, Bonaparte assured them that he would prevent French soldiers from attacking the population and harming their interests, and would not impose taxes, abuse, plunder, or threats, and that the violator would receive the most severe punishment. Accordingly, a delegation of Bedouin knights came and presented forty prisoners, and Bonaparte rewarded them with gifts, but when they left, you attacked a group and killed four of them because the peace agreement did not reach them.

Bonaparte’s announcement to reassure the people of the country, on the one hand, sparked laughter from the soldiers who saw Bonaparte assuming the role of the messenger. On the other hand, the Bedouins were not deceived by Bonaparte’s promises, and did not miss the opportunity to respond intelligently to what he claimed: “You say that you have come to protect us and eliminate the Mamluks, and you descend with your forces secretly and shoot us.”

Thus we see that the people of Alexandria were not deceived by Bonaparte’s promises, and the resistance will continue under the leadership of Muhammad Karim, the Sharif of Alexandria. Muhammad Karim, the Sharif of Alexandria, was the largest ruler in Alexandria when the French came, and he was in charge of customs administration. After seizing the city, Bonaparte wanted the people of the country to participate in governance, and he gathered sheikhs from the Al-Hanadi, Awlad Ali, and Bani Yusuf tribes, and the city’s notables, and asked them to reform the situation. The country, and asked them to be loyal to the French Republic, and pledged to make the road from Alexandria to Damanhour safe, supply the army’s needs in terms of horses and camels, and to release the French prisoners they had captured when they captured Alexandria.

Within the framework of this reconciliation, Muhammad chose Karim for his courage in the fight against the French, and appointed him governor of one of the districts under Kléber’s administration. He allowed him – if necessary – to contact him directly, and said to him: “You took the weapon in your hand, and I had the right to I treat you like a prisoner, but you have been valiant in defense, and courage goes hand in hand with honor, so I return your weapon to you, and I hope that you will show to the French Republic as much loyalty as you showed to a bad government.”

After the capture of Alexandria, Bonaparte took measures to march the army to Cairo, and left Alexandria on July 7 to join the forces after he issued the order appointing General Kléber, who was wounded during the attack, as commander of the territory of Alexandria and its environs.

Bonaparte’s escape:

Bonaparte thought about leaving Egypt and returning to France when he wrote to his brother Joseph on July 25 to buy him a house and to stand by him for his psychological conditions, as he learned of Josephine’s betrayal. The defeat of the naval battle of Abu Qir prevented him from traveling, and he became a prisoner in Egypt, so he could not return unless victorious. The victory of the land battle of Abu Qir over the Turks a year later was an opportunity for a comeback, especially since the French armies were defeated in Europe by Russia and Austria. He said, “I am not disappointed. The miserable people have lost Italy. All the results of the army’s victories are lost. I must leave.”

He saw that his mission in Egypt had ended, and Egypt had become a secondary topic, and he believed that he was qualified to preside over the French Republic. In Paris, people were demanding the return of the victor in Italy, as if the campaign against Egypt did not concern them.

Bonaparte gathered travelers and asked the admiral to prepare ships and provisions for the journey of four or five hundred people.

Bonaparte had all the powers, chose his men, and asked them to keep the secret so that the English would not know. He did not wait for Kleber, who was meeting with him. Perhaps he was afraid that he would cause him some problems because he saw in him a capable competitor. The evidence is that he appointed him as commander of the Eastern Army to replace him, and assigned General “Mino” the task of handing him his appointment papers, and asked him to wait forty-eight hours. Until he leaves Alexandria.

According to Nicholas Turk’s testimony, Bonaparte prepared boxes loaded with jewels, luxury weapons, fabrics, and what he had acquired in wars, and took with him some young Mamluks. He said that Bonaparte cleverly flew out of its cage like a bird to avoid the English.

He left the decree of June 22, 1798 AD, to remind Kleber of the importance of internal politics in Egypt, to eliminate differences due to religion, and to try to suppress fanaticism until we extract its roots.

The Arish agreement was reached, but the British wanted to remove the French army as prisoners, and with the courage of the warrior, he defeated them in the Battle of Heliopolis (Ain Shams). He believed that the campaign was not political and had no purpose, and the French only came to fight the English and their possessions in India, and impose peace.

Execution of Muhammad Karim:

At first, Karim performed his duty and showed cooperation with Kleber, but Kleber discovered that he was behind the conspiracies, rumors, and confusion. Several events occurred, and Kleber realized Karim’s role in leading the resistance against the French. Including an artillery soldier being attacked, and another soldier being killed by drowning. Kleber asked the sheikhs to hand over the accused, and took some of the notables of Alexandria hostage, and Karim’s brother was among them.

In another incident, the moving forces heading to Damanhour were attacked by the Bedouins, and it became clear that Karim was leading these disturbances. We find in Kleber’s correspondence details of positions against the French. Kleber made his decision to expel Karim from Alexandria, but he respected Bonaparte’s decision, who trusted him and appointed him to help him.

Kléber wrote a letter to Karim stating that matters could not be managed with dual presidency, and asked him to join the Supreme Commander Bonaparte, whom he wanted to approach. He sent him on a ship to Abu Qir to detain him on the battleship Lorient, and recommended that Admiral “Bruis” treat him well, and send the admiral to Rashid. As soon as he arrived there, an uprising broke out among the people of the city welcoming Karim, so “Mino” was forced to imprison him and deport him to Cairo. Kléber wrote to Bonaparte assuring him that Alexandria was safe, there were no disturbances, and life was stable since Karim’s absence.

Karim was investigated, and Napoleon issued his order on September 5, 1798, to execute Karim by firing squad, confiscate his money and property, and allowed him to ransom himself by paying a fine of 30,000 riyals within 24 hours. There are many stories here, whether he refused to pay the ransom amount and showed fortitude and courage in the face of the death sentence.

It is said that Bonaparte’s chief translator, the orientalist Venture, advised him to pay the fine, and said to him: You are a rich man, so what harm would it do you if you ransom yourself from death with this amount? Muhammad Karim replied to him: If he was destined to die, he would not be protected from death by paying. If he is able to live, why should he pay this amount? He remained persistent until he was executed by firing squad in Rumaila Square in Cairo on September 6, 1798 AD.

Al-Jabarti describes the scene of the execution:

“When it was near noon, and the deadline had passed, they mounted him on a donkey, and a number of soldiers surrounded him with drawn swords in their hands, and a drum was beating on him in front of them, and they tore through the Saliba neighborhood with it, until they went to Rumaila, and they shouldered him and tied him with a scarf, and they beat him with rifles as is their custom for those who cast new lights. On an important and unknown event at the beginning of the French campaign against Egypt (1798-1801), during the rise of Bonaparte, crowned with the glories of his victory in Italy, they killed him, then cut off his head, raised it on a pedestal, and paraded it around Rumaila, and the herald said:

This is the punishment for those who disobey the Francis. Then his followers took his head and buried it with his body, and his matter ended, on Thursday the fifteenth of Rabi’ al-Awwal.”